ga;ns: Toward Better Code Review

2024-01-05

Alice (senior engineer) and Bob (junior engineer) work together building software. Today, Bob is interested in getting code review from Alice.

Here’s what happens:

BOB (PR AUTHOR)

Writes code, commits, pushes, & opens PR.ALICE (PR REVIEWER)

Sees PR was opened, starts reviewing. After reviewing some of the changes, she’s wondering about an alternative approach. She leaves a comment: “What would you think about [making change X]?”BOB

Sees Alice’s comment. But he doesn’t reply, instead he goes ahead and [makes change X], commits, pushes.ALICE

Sees that Bob went ahead and just [made change X] instead of replying. But in actuality, when she asked “What would you think?” she was genuinely asking a question, and genuinely curious about what Bob thought…“Hmm, I wasn’t really expecting that,” she thinks.

After a moment, she says to herself: “Ok, since Bob committed [change X], he must believe it was the right change. All good.”

Review continues like this, with Alice commenting & Bob committing. In fact, most of Bob’s PR reviews go like today’s. So it’s a pretty usual day for Bob. Alice usually has great suggestions, and Bob usually enjoys hearing them. Eventually, after a few more comments & commits, the pipeline is green, the PR is approved, and so Bob merges it. All’s well, then.

Yet something remains unresolved: A conversation that could have happened, did not happen.

Missed connections

So was [change X] the best change to make? Who could know?

Moreover: Does Alice & Bob’s day sound familiar to you? Have you been in a situation like this before? I certainly have.

And if you have, I’d guess that you likely identify with Alice’s position rather than Bob’s. What Bob perceives is a typical day — and it may be completely unremarkable to him. But what Alice recognizes is conflict between what she intended and what Bob perceives. So if you relate more to Alice, I believe it is because we tend to recognize and recall what is in conflict more than what is unremarkable.

After all, isn’t that what we are doing in code review anyway? As reviewers, we are primed to scan patterns for the flaws in the code. And as authors, we are primed to understand the flaws and fix the code.

But despite our diligence in fixing the code, we might be missing another thing that needs fixing: The hidden conflicts in how we communicate about the code.

Etiquette as a feature & etiquette as a bug

When we talk about “culture fit” we are really looking to minimize the delta between the behaviors and expectations in the network in order to become efficient. Etiquette develops.

As a reviewer, we learn to ask questions instead of make demands. And we are advised that the questions we ask should be open-ended. For example, the following questions share intent, but vary in their open-endedness:

“Could we name this

fooinstead ofbar?”

“Are there other names we can use than

bar?”

“The name

barmay cause issues because [SOME LENGTHY EXPLANATION]. I was thinkingfoomight be better, but I’m not sure. I’d love to hear more about why you believebaris the best name, and what your thoughts are about [THE LENGTHY EXPLANATION]. Can you share them?”

So we can certainly assert that Alice’s question wasn’t very open-ended. Fair. We can argue that Alice can do better.

Unfortunately, my experience has been questions like Alice’s are typical in review, especially if Alice is learning to develop her skills as a reviewer, or even if Alice is simply constrained for time.

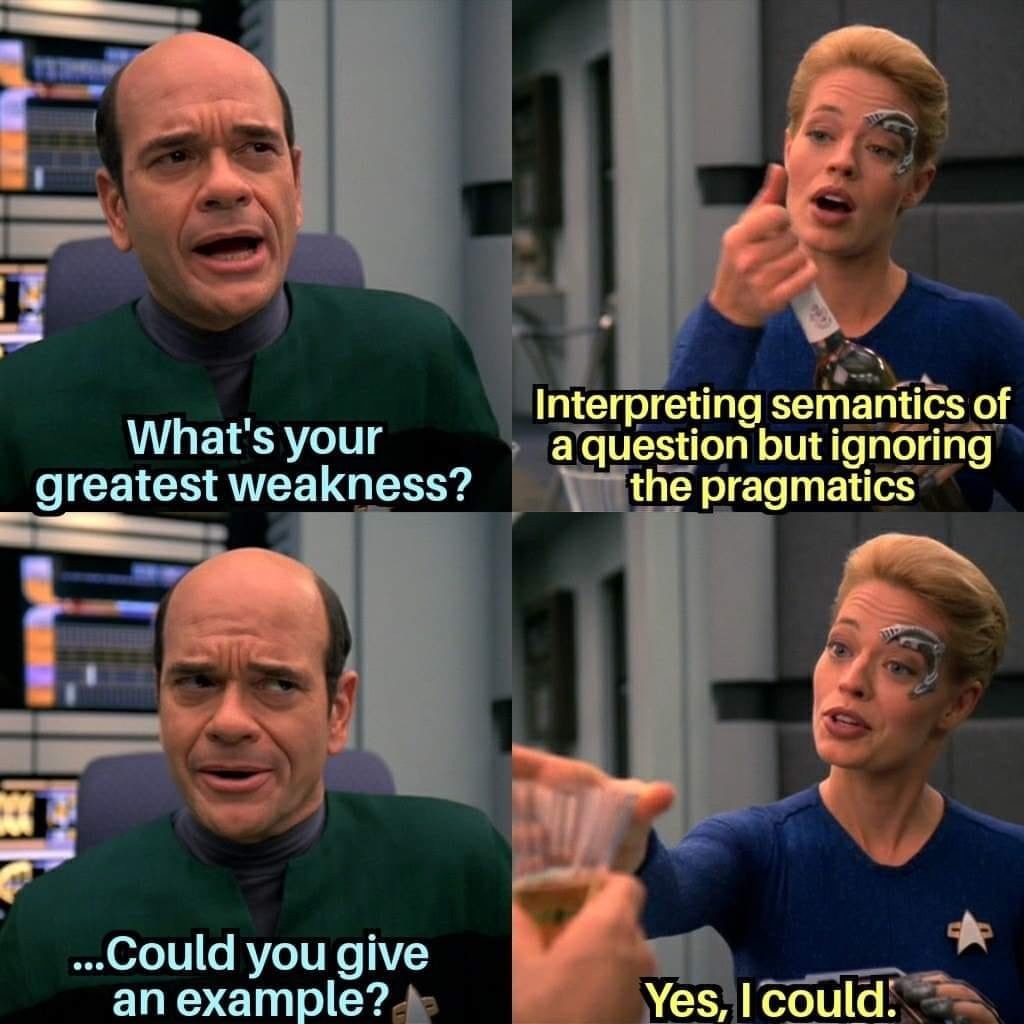

And as mentioned, the very task of code review itself primes both author and reviewer to “find-flaws-and-fix.” So alongside our varying skills and efforts, a typical question asked in review is often not perceived as a question at all, but instead as a polite suggestion.

I have found this is especially prevalent in when a less experienced engineer is receiving review from a more experienced engineer. After all, part of Junior Engineer Bob’s job is to grow by learning from people like Senior Engineer Alice, right?

BOB

“Alice wants me to [make change X], and she is being polite instead of demanding. I’ll go ahead and make it,” he thinks.

Can we fault him? I don’t think we can.

Bob and Alice have much in common. They share skills, culture, and etiquette. Their wants are compatible: Alice wants to ask, not suggest; Alice wants to be understood; Bob wants to understand. But despite all this, they experience communication mismatch.

We can posit any number of ideas to improve today’s review — to have the conversation that was not had.

Alice could have asked a more open-ended question. Bob could have interrogated further whether Alice was making a suggestion. And Alice could have reached-out to Bob after he [made change X] and clarified her intent.

I’m compelled to ask: Is there a shortcut? I think there could be.

ga;ns == “Genuinely Asking; Not Suggesting”

The next time we are in Alice’s seat, and we are writing that PR comment, may I propose the following: Let us explicitly state that we are genuinely asking about something to gain context and we are not suggesting to make something proceed without further context. We can use ga;ns for short.

Think of it as the inverse of tl;dr — as readers, we signal simply we’re looking for more context — to give our transactional pragmatics a respite, and possibly discover something we’d otherwise pass over.

If this appeals to you, when you leave your PR comments, link ga;ns to this post. Maybe it will catch on as a new entry in our etiquette.

If it does, perhaps we begin finding conversations gone missing. And hopefully a found conversation makes for better code review, and better code.